Benchmarks as Limits to Arbitrage: Understanding the Low-Volatility Anomaly

- Baker, Bradley and Wurgler

- A version of the paper can be found here.

- Want a summary of academic papers with alpha? Check out our Academic Research Recap Category.

Abstract:

Contrary to basic finance principles, high-beta and high-volatility stocks have long underperformed low-beta and low-volatility stocks. This anomaly may be partly explained by the fact that the typical institutional investor’s mandate to beat a fixed benchmark discourages arbitrage activity in both high-alpha, low-beta stocks and low-alpha, high-beta stocks.

Alpha Highlight:

Empirical research shows that low-volatility stocks earn higher risk-adjusted returns than high-volatility stocks. An anomaly that flips the entire financial economics profession on hits head.

We’ve done some simple tests with the strategy in the following posts:

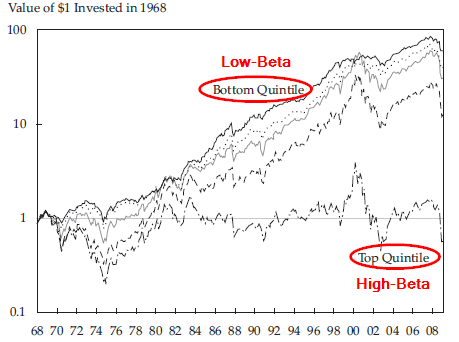

This paper verifies the existence of low-vol anomaly. Data is obtained from CRSP, and ranges from 1968 to 2008. The paper sorts stocks into five groups for each month according to their 5-year trailing total volatility or trailing beta. The figure below shows the performances of the 5 groups of stocks. The conclusion is clear: Low-beta stocks outperform high-beta stocks.

But How is this Possible?

Part 1: Bad Investor Behavior

The preference for high-volatility stocks derives from the biases that afflict the individual investor.

(1) Preference for lotteries. Here’s a good example from the paper:

- A 50% chance of losing $100 vs. a 50% chance of winning $110;

- A near-certain chance of losing $1 and a 0.0099 percent chance of winning $10,000. (Gamble: low-priced but volatile)

Which bet will you take? Although the first choice has a positive expected payoff, most people prefer the second one with the negative expected payoff. Here’s how the paper explains the finding:

Buying a low priced, volatile stock is like buying a lottery ticket: There is a small chance of its doubling or tripling in value in a short period and a much larger chance of its declining in value.

(2) Representative Bias: Another example from the paper: Investors purchased Microsoft Corp. and Genzyme Corp. at their IPOs in 1986, which were considered “great investments.” However, people’s representative bias leads them conclude that “the road to riches is paved with speculative investments.” So investors are inclined to overpay for volatile stocks and ignore the failures of other speculative investments.

(3) Overconfidence: Both normal people and finance professionals suffer from overconfidence, or the inability to appropriately calibrate forecasts. Overconfidence enhances disagreement around stock price forecasts, especially for stocks with more uncertainty, such as high-vol stocks.

Part 2: Limits of Arbitrage

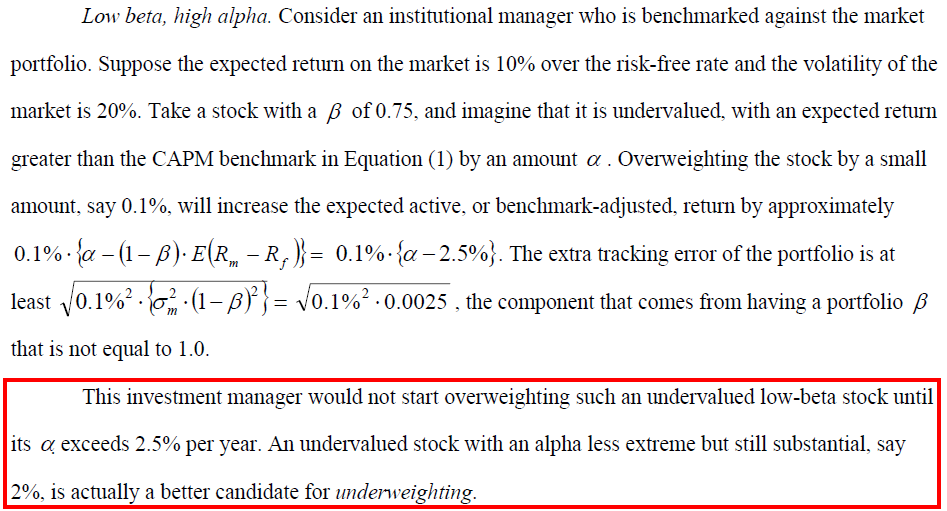

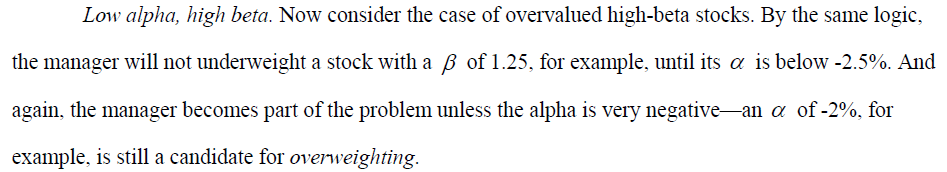

An institutional investor with a fixed benchmark is surprisingly unlikely to exploit such mispricings. In fact, in empirically relevant cases, the manager’s incentive is to exacerbate them.

The paper hypothesizes that the presence of delegated investment management with a fixed benchmark causes the CAPM relationship to fail. A quote from the paper is below:

Conclusion

In a nutshell, the paper reviews the low-volatility anomaly through the lens of behavioral finance: understand how behavioral bias is affecting an asset’s price and understand why large pools of capital aren’t exploiting this biased behavior (in this case the large pools of capital are increasing the bias!).

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.