Contagious Speculation and a Cure for Cancer: A Nonevent that Made Stock Prices Soar

- Gur huberman and Tomer Regev

- A recent version of the paper can be found here.

Abstract:

A Sunday New York Times article on a potential development of new cancer-curing drugs caused EntreMed’s stock price to rise from 12.063 at the Friday close, to open at 85 and close near 52 on Monday. It closed above 30 in the three following weeks. The enthusiasm spilled over to other biotechnology stocks. The potential breakthrough in cancer research already had been reported, however, in the journal Nature, and in various popular newspapers (including the Times) more than five months earlier. Thus, enthusiastic public attention induced a permanent rise in share prices, even though no genuinely new information had been presented.

Data Sources:

The authors exam the New York Stock Exchange Trade and Quotes (TAQ) database for intraday data, prices, and quotes. They also use CRSP data for daily returns and information found in SEC filings. This paper does not involve heavy database use and could be replicated with any number of data sources.

Discussion:

The semi-strong form of the efficient market hypothesis is straightforward: stock prices immediately reflect all publicly available information. Simple enough. Microsoft comes out with news they found a $100billion in cash sitting in a garage, the stock price should move up by around $100billion almost immediately.

The problem with the semi-strong efficient market hypothesis is that it is too simple. It makes a key assumption–collecting, understanding, and rationally synthesizing public information is easy, fast, and cheap. Anyone who has read thousands of pages of SEC documents and spent hours on the phone with a company’s management trying to understand the intricacies of the business and public statements knows otherwise. It seems a bit contrived that investors somehow have a super-human ability to digest massive amounts of new information in a quick, unbias, and cheap way. This doesn’t even include the fact that even IF there were some investor with superhuman ability, the limits of arbitrage may keep him from placing his bet.

This paper highlights just how silly the semi-strong market hypothesis can be in certain circumstances. The reality is that public information isn’t always perfectly reflected in a stock’s price. Moreover, this work shows that the most important aspect of information is not the actual information, but the messenger of the information.

In the case study highlighted by the authors, some weird things happen to ENMD–EntreMed.

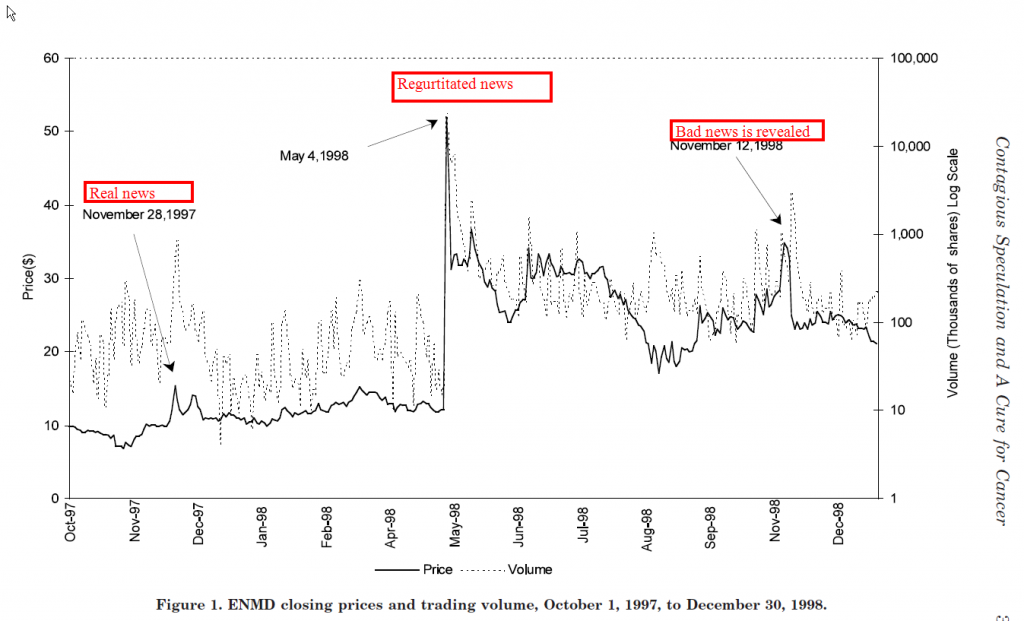

First, on November 28, 1997 research is published in Nature (mentioned in Time magazine as well) regarding a recent breakthrough in cancer research that is related to ENMD’s prospects. From the chart below, one can see that the market certainly reacts to the initial news.

Then on May 4, 1998, the New York Times releases an article that essentially regurgitates the news and information that was released on November 28, 1997, in the Nature article. As the chart shows, the stock sky-rocketed!

Finally, on November 12, 1998, the Wall Street Journal reports that the results in the original Nature article cannot be replicated by other research labs–the stock plummets.

Interestingly, even after the stock plummets in Nov 1998, the stock still remains 200% higher than when the original news was reported in Nature.

What in the world is going on here? We’ll probably never know, but we do know one thing: as long as information costs and synthesis are not free, the semi-strong market hypothesis doesn’t hold water.

Investment Strategy:

The optimal investment strategy here is not clear-cut. The point of this post is to get us thinking about systematic ways to take advantage of future EntreMed situations.

Here is a suggested avenue of approach that one might explore:

- Identify scientific journals and/or niche trade journals where companies discuss new breakthroughs or products that can have significant impacts on shareholder value (e.g. Nature).

- Determine if it can be verified that the efficient market hypothesis is likely to have failed (i.e. information is limited to a small audience and/or difficult to digest for typical investor).

- Work on information dissemination–force the semi-strong efficient market hypothesis to come true. (i) draft an interesting story for public dissemination, (ii) query editors and/or journalists, (iii) post on blogs, message boards, and other outlets followed by investors.

- Ride the wave.

It always sounds so easy in theory…

Commentary:

This paper is a bit outside the box from our typical post, but we think it is important. I know it got me thinking about new trading ideas and ways to approach the market, so I’m sure it will help our readers out as well.

Good luck.

About the Author: Wesley Gray, PhD

—

Important Disclosures

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as specific investment, accounting, legal, or tax advice. Certain information is deemed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Third party information may become outdated or otherwise superseded without notice. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) nor any other federal or state agency has approved, determined the accuracy, or confirmed the adequacy of this article.

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Alpha Architect, its affiliates or its employees. Our full disclosures are available here. Definitions of common statistics used in our analysis are available here (towards the bottom).

Join thousands of other readers and subscribe to our blog.